A developer who purchased a 500-acre island property in St. Helena Island, SC, keeps re-working his plans to develop a golf community there as local officials keep denying them. At issue is the protection of the centuries old Gullah-Geechee community whose descendants still farm the land and own other businesses there.

A decades-old zoning law on St. Helena Island bans golf carts, resorts and gated communities in an area that the enslaved Gullah-Geechee people, descended from Central and West African societies, settled as farmers and merchants at the end of the Civil War. The law was enacted to protect the Gullah-Geechee from the kind of development that had earlier pushed them out of other coastal areas like Daufuskie Island just to the east of Hilton Head, and Hilton Head itself. An estimated population of one million Gullah peoples live along the Southeast coast, but their populations are diminishing.

Developer Elvio Tropeano moved to St. Helena a few years ago and, earlier this year, purchased the land on St. Helena called Pine Island with the idea of building a golf course and luxury homes. Since then he, and dozens of concerned local citizens, have appeared before meetings of the town’s zoning commission. The arguments from both sides goes like this: Local groups object to the development because chemicals that are sure to be used on the golf course will leech into the local waterways and farmland and destroy the local Gullah people’s farms; and the 160 luxury homes Tropeano intends to build will increase property taxes. Ruining their farms and raising their taxes, the reasoning goes, will drive the Gullah from the area just as it did on Hilton Head and Daufuskie Islands.

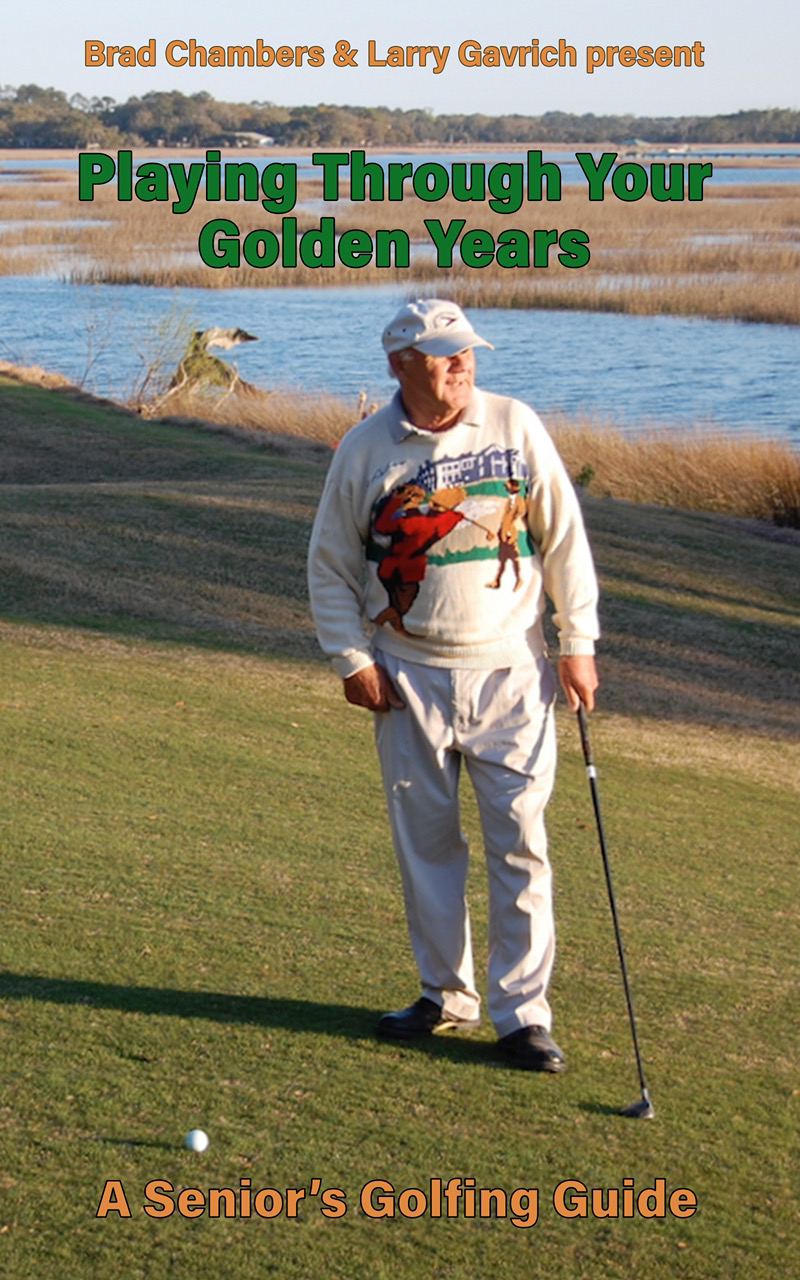

The Dataw Island golf community is just six miles from the controversial zoning issues on St. Helena Island. With its 36 holes and mature population, the community should not see any big development nearby as a threat.

The Dataw Island golf community is just six miles from the controversial zoning issues on St. Helena Island. With its 36 holes and mature population, the community should not see any big development nearby as a threat.Tropeano counters by asking a rhetorical question at the local meetings: “How do I create recognition and generate resources in a manner that does not displace people?” Fair enough but, publicly, he has responded that if things don’t go his way with the golf course development, he will go ahead and build his 160 luxury homes and add 90 deep-water docks. That’s no way to win friends and influence people. His latest response to concerns about the golf course was to suggest he build three six-hole layouts on different parcels of land. As one of the Gullah supporters said in a local media report, “A golf course is a golf course, no matter how small.” The Battle of St. Helena Island goes on. (Here’s one local article about it.)

Meanwhile, a mere six miles away, the well-established golf community of Dataw Island must be looking on with some interest, if not concern. Dataw, which is home to two excellent golf courses -- one by Tom Fazio, the other by Arthur Hills -- and a beautiful low-country location, was opened in the mid 1980s. Located less than a half hour from the charming southern town of Beaufort (byou-fert) and the same distance from an Atlantic Ocean beach at Hunting Island, Dataw Island splits the difference between quiet, pollution and traffic-free living with access to the kinds of lifestyle embellishments retirees look for in a forever golf home. (I visited and published a full review of the Dataw Island golf community in 2015.)

Currently, local Dataw listings are showing five homes for sale and 15 homesites. The homes are listed from $439K to $875K, and the lots from $23,900 (that one is located on the Fazio golf course). If you want more information about Dataw or a referral to the highly qualified real estate agent I work with there, please contact me.